When you hear someone say they have obesity, it’s easy to think it’s just about weight. But for millions of people, especially in the U.S., obesity is the starting point for a dangerous chain reaction - one that often leads to diabetes, heart disease, and sleep apnea. These aren’t just separate conditions you might happen to have. They feed off each other. One makes the others worse. And together, they create a cycle that’s hard to break without understanding how they’re linked.

How Obesity Sets Off the Chain Reaction

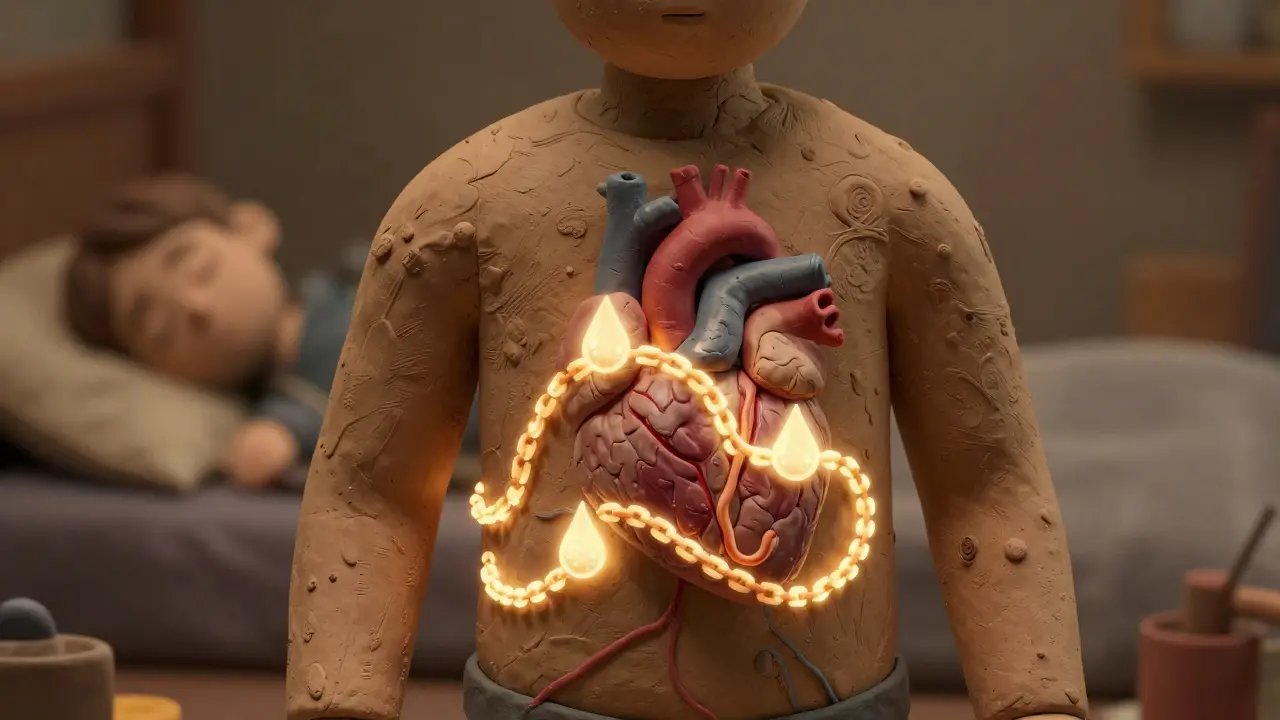

Obesity isn’t just extra pounds. It’s a metabolic disruption. When your body stores too much fat - especially around your belly - it starts releasing chemicals that cause inflammation. This isn’t the kind of inflammation you feel after a workout. It’s quiet, constant, and damaging. That inflammation messes with how your body uses insulin, clogs your arteries, and even narrows your airways while you sleep. The numbers don’t lie. In the U.S., over 42% of adults have obesity (BMI ≥30). And among those people, the odds of developing one of these three conditions skyrocket. The SLEEP-AHEAD study found that 86% of obese people with type 2 diabetes also had sleep apnea. That’s not coincidence. That’s cause and effect.Diabetes: The Metabolic Domino

Fat tissue, especially visceral fat around your organs, doesn’t just sit there. It acts like a hormone factory, pumping out substances that make your muscles and liver resistant to insulin. That means your pancreas has to work harder to keep your blood sugar down. Eventually, it burns out. That’s when type 2 diabetes kicks in. But here’s the twist: diabetes doesn’t just come from obesity - it makes obesity harder to manage. High blood sugar damages nerves, including those that control your airway muscles. That’s one reason why people with diabetes are more likely to develop sleep apnea - even if they lose some weight. And when you add insulin resistance to the mix, your body holds onto fat more tightly. It’s a loop: obesity → insulin resistance → diabetes → worse fat storage → worse sleep apnea. The data is clear: severe sleep apnea increases your risk of developing type 2 diabetes by 60%, even after accounting for your weight. And if you already have diabetes, untreated sleep apnea can make your HbA1c levels rise by 0.8% or more - enough to push you out of good control and into danger zone.Sleep Apnea: The Silent Aggressor

Sleep apnea isn’t just loud snoring. It’s when your airway collapses during sleep, stopping your breathing for 10 seconds or more - sometimes hundreds of times a night. In obese people, fat builds up in the neck, tongue, and throat. That’s like stuffing a straw with cotton. Your airway gets smaller. Your body wakes up just enough to gasp for air - but you don’t remember it. You just feel exhausted all day. The Wisconsin Sleep Cohort Study found that for every extra point in your BMI, your risk of sleep apnea goes up by 14%. But waist size matters even more. Each extra centimeter around your waist increases your risk by 12%. That’s why two people with the same BMI can have very different sleep apnea risks - it’s not just weight, it’s where the fat is. And here’s what most doctors miss: sleep apnea doesn’t just make you tired. It spikes your blood pressure every time you stop breathing. Those nighttime surges can be 15-25 mmHg. Over years, that wears out your heart. It thickens your heart muscle, raises your risk of atrial fibrillation, and makes your blood clot more easily. The American Heart Association calls sleep apnea a modifiable risk factor - meaning if you treat it, you can cut your chances of a heart attack or stroke.

Heart Disease: The Deadly Endgame

Put diabetes, sleep apnea, and obesity together, and you’ve got the perfect storm for heart disease. Each one damages your cardiovascular system in different ways:- Obesity causes your heart to enlarge - up to 20% bigger - just to pump blood through extra tissue.

- Sleep apnea triggers sudden spikes in blood pressure and stress hormones every night.

- Diabetes speeds up plaque buildup in your arteries, making them stiff and narrow.

Why This Triad Is Often Missed

Here’s the heartbreaking part: most people don’t realize these conditions are connected. A patient goes to their endocrinologist for diabetes. They see a cardiologist for high blood pressure. They complain to their primary care doctor about being tired all the time. But no one connects the dots. A 2022 survey by the Obesity Action Coalition found that 74% of obese people with diabetes and sleep apnea felt exhausted at work. Over 40% had near-miss car accidents because they couldn’t stay awake. Yet, 68% of them waited 5 to 7 years before getting diagnosed with sleep apnea. Doctors often focus on treating one condition at a time - lower your sugar, lower your cholesterol, lose weight. But they rarely ask: Do you snore? Do you wake up gasping? Do you fall asleep in the car? If they did, they’d find that 60-80% of obese diabetic patients have undiagnosed sleep apnea.How to Break the Cycle

The good news? You don’t have to live with all three. Treating one can help the others.- CPAP therapy - the standard treatment for sleep apnea - doesn’t just help you sleep. A 2021 study in Diabetes Care showed that consistent CPAP use for six months lowered HbA1c by 0.8% and led to an average weight loss of 3.2 kg - even without diet changes.

- Weight loss is the most powerful tool. Losing just 10-15% of your body weight cuts sleep apnea severity by half. In one study, people who lost that much saw their apnea-hypopnea index drop by over 25 events per hour.

- Bariatric surgery isn’t for everyone, but for those with severe obesity and diabetes, it leads to remission of sleep apnea in 78% of cases.

- New medications like semaglutide (Wegovy, Ozempic) don’t just help you lose weight - they reduce fat in your airway, improving sleep apnea even before the scale moves much.

The Hard Truth About Treatment

None of this works if you don’t stick with it. Only 45% of people with sleep apnea keep using their CPAP machine after one year. Why? Masks feel claustrophobic. The air pressure is uncomfortable. It’s noisy. People get frustrated. But there are options. Newer CPAP machines are quieter, lighter, and come with heated humidifiers. For those who can’t tolerate CPAP, there’s the Inspire device - a small implant that stimulates the nerve controlling your tongue, keeping your airway open. Clinical trials show 79% of users cut their apnea events in half. And while weight loss is the most effective long-term fix, it’s also the hardest. That’s why coordinated care matters. You need a team: a doctor who understands metabolism, a sleep specialist, a dietitian, and maybe a therapist who helps with behavior change. Kaiser Permanente’s integrated program reduced hospital visits by 18% in just one year by treating all three conditions together.What You Can Do Today

If you have obesity and one of these conditions, ask yourself:- Do I snore loudly or stop breathing during sleep?

- Do I wake up with a dry mouth or headache?

- Do I feel exhausted even after a full night’s sleep?

- Has my doctor ever asked me about my sleep?

Jane Lucas

December 28, 2025 AT 04:40ive been tired all the time and thought it was just stress but now i realize i might have sleep apnea

Kishor Raibole

December 28, 2025 AT 14:46It is, without question, an egregious oversimplification to attribute the entirety of metabolic dysfunction to adipose tissue accumulation. The pathophysiological underpinnings of such comorbidities are profoundly multifactorial, encompassing genetic predisposition, epigenetic modulation, and socioenvironmental determinants that are systematically neglected in reductionist narratives.

One must interrogate the underlying epistemological framework of public health discourse, which often pathologizes bodily diversity under the guise of medical necessity. The conflation of BMI with health outcomes is a relic of 20th-century epidemiology, ill-equipped to address the complexity of human physiology.

Furthermore, the commercial interests driving the bariatric and pharmaceutical industries cannot be divorced from the promotion of these diagnostic paradigms. The assertion that CPAP therapy yields weight loss is statistically confounded by selection bias and lacks longitudinal validation.

It is not merely a matter of intervention, but of ideological framing: who benefits from labeling obesity as a disease? Who profits from the proliferation of medical devices and pharmacological regimens? The answer is not the patient, but the system.

One must also consider the psychological toll of constant medical surveillance. The internalization of shame as a motivator for health is a form of coercive medicine that undermines autonomy.

While the data presented is methodologically sound, its interpretation is ideologically loaded. Health is not a binary state between ‘normal’ and ‘pathological.’ It is a spectrum, and the medical establishment has long failed to respect that nuance.

Let us not mistake correlation for causation, nor statistical association for moral imperative. The body is not a machine to be optimized, but a living, evolving system deserving of dignity, regardless of its shape.

Kylie Robson

December 30, 2025 AT 05:21Let’s be precise: visceral adipose tissue secretes adipokines like leptin and resistin, which induce systemic insulin resistance via JNK and IKKβ/NF-κB inflammatory cascades. The resulting hyperinsulinemia promotes lipogenesis and suppresses lipolysis, creating a feed-forward loop. Simultaneously, hypoxia in expanded adipose tissue triggers HIF-1α upregulation, further exacerbating endothelial dysfunction and sympathetic overactivation.

Obstructive sleep apnea isn’t merely mechanical-it’s a chronic intermittent hypoxia (CIH) model that induces oxidative stress, carotid body sensitization, and baroreflex impairment, which directly contribute to nocturnal hypertension and cardiac remodeling.

The 0.8% HbA1c reduction with CPAP? That’s clinically significant-equivalent to adding metformin. And semaglutide’s GLP-1 receptor agonism not only reduces appetite but also decreases hepatic lipid accumulation and improves upper airway muscle tone via central nervous system modulation.

The real issue? Most clinicians still treat these as siloed conditions. We need integrated metabolic-cardiopulmonary clinics with shared EHR protocols and standardized STOP-Bang + HOMA-IR screening at every BMI ≥30 encounter.

And yes, the 45% CPAP adherence rate is abysmal-but that’s a behavioral health problem, not a device failure. We need AI-driven compliance coaching, not just masks.

Elizabeth Alvarez

December 30, 2025 AT 07:24They don’t want you to know this, but obesity is being used as an excuse to push surveillance tech and pharmaceutical control. Did you know that CPAP machines are linked to cloud-based health platforms that track your breathing patterns and sell the data to insurers? They use your sleep apnea to raise your premiums.

The whole diabetes-obesity-heart disease link? A marketing scheme cooked up by Big Pharma and MedTech to sell drugs, devices, and endless checkups. They don’t care if you live or die-they care if you keep buying.

And what about the sleep studies? They’re rigged. The machines are calibrated to overdiagnose so they can sell you more gear. The FDA doesn’t regulate these devices like they do real medicine. They’re classified as ‘low risk’-same as tongue depressors.

They’re also pushing these new weight-loss drugs because they’re expensive and profitable. Semaglutide? It’s not a cure. It’s a lifelong subscription. And if you stop? The weight comes back faster than ever.

They want you dependent. They want you afraid. They want you to believe your body is broken so you’ll keep paying for fixes that don’t fix anything.

There’s a reason they never talk about poverty, food deserts, or shift work. Those are the real causes. But those don’t make money. Only pills and machines do.

Wake up. Your sleep apnea isn’t from fat. It’s from the stress of living in a system that sees you as a profit margin.

Miriam Piro

December 31, 2025 AT 08:44They’re lying to us. The whole medical industrial complex is built on making people feel broken so they’ll buy solutions. Obesity isn’t a disease-it’s a symptom of a society that’s poisoned us with processed food, stress, and sleep deprivation.

But they won’t fix the food system. They won’t fix our 12-hour workdays. They won’t fix the fact that the only ‘healthy’ food costs 3x more than a bag of chips. So instead, they sell you a $5,000 CPAP machine and tell you to ‘just lose weight.’

And don’t get me started on semaglutide. It’s not medicine-it’s a chemical leash. They’re turning human bodies into products to be managed, not lives to be lived.

Meanwhile, the real solution? Community gardens. Paid parental leave. Universal healthcare. Free sleep clinics. But those would cost money. And corporations won’t let that happen.

They don’t want you healthy. They want you compliant. And if you’re too tired to fight back? Perfect. That’s the goal.

Look at the data. Countries with universal healthcare and food security have lower obesity rates-not because they’re better at medicine, but because they’re better at living.

We’re being gaslit by doctors who don’t have time to listen. We’re being sold a lie: that your body is your fault. It’s not. It’s the system.

dean du plessis

January 1, 2026 AT 18:27Man, I used to think being tired was just part of getting older. Then I started noticing I’d nod off watching TV even if I slept 8 hours. My wife said I snore like a chainsaw. I never connected it to my high blood sugar or my waistline.

But I went to the clinic last month and got the STOP-Bang test. Scored 5. Did the sleep study. Yep-moderate apnea. Started CPAP. First week was rough. Felt like a robot with a mask. But now? I wake up feeling human again.

Lost 8 lbs without trying. My sugar’s better. I’m not snapping at my kids anymore.

It’s not magic. It’s just listening to your body when it screams.

James Bowers

January 3, 2026 AT 01:34The author’s assertion that weight loss is the ‘most powerful tool’ is not merely misleading-it is dangerously simplistic. The literature consistently demonstrates that intentional weight loss through behavioral intervention has a long-term failure rate exceeding 95%. To frame obesity as a modifiable behavioral defect is to engage in moralistic pseudoscience.

Furthermore, the recommendation to screen all obese patients for sleep apnea constitutes a form of medical overreach. The STOP-Bang questionnaire has a high false-positive rate in asymptomatic populations, leading to unnecessary polysomnography and subsequent iatrogenic anxiety.

It is ethically indefensible to promote CPAP as a panacea when adherence is suboptimal and the long-term cardiovascular benefits remain contested in meta-analyses.

The real solution lies not in medicalizing the body, but in addressing the structural determinants of health: economic inequality, food deserts, and occupational stress. Until then, such recommendations are not healthcare-they are social control disguised as science.

Will Neitzer

January 4, 2026 AT 11:17This is exactly why integrated care models are the future. Too often, patients are passed between specialists like a relay baton-endocrinologist, cardiologist, pulmonologist-each treating their piece of the puzzle while the bigger picture fades.

At our clinic, we now have a ‘Metabolic Health Navigator’ role-a non-physician care coordinator who works with patients to link their diabetes management, sleep apnea treatment, and nutritional counseling under one unified plan.

We don’t just hand out a CPAP machine and say ‘come back in six months.’ We schedule weekly check-ins, offer mask fitting workshops, connect patients with dietitians who specialize in insulin resistance, and even provide free transportation to sleep labs.

And the results? Adherence to CPAP jumped from 42% to 71% in 18 months. HbA1c dropped an average of 1.4%. And patients reported feeling less isolated, less judged, and more in control.

This isn’t about blame. It’s about building systems that actually support people. We have the tools. We just need the will to use them together.

Caitlin Foster

January 6, 2026 AT 09:27OMG I literally just got diagnosed with sleep apnea last week and I was like ‘wait… so I’m not just lazy??’ 😭

My doctor said ‘maybe try CPAP’ like it was a suggestion… I was like NO I WILL NOT WEAR A MASK TO BED UNTIL YOU TELL ME WHY THIS IS LIFE OR DEATH.

Then I read this and cried. I’ve been falling asleep in meetings since 2020. My husband says I stop breathing. My sugar’s been creeping up. I thought it was just ‘adulting’.

Today I ordered my CPAP. And I’m telling my whole family. This isn’t just about sleep-it’s about staying alive.

YOU ARE NOT ALONE. I’M RIGHT HERE WITH YOU. 💪❤️

Chris Garcia

January 8, 2026 AT 02:01In my village in Nigeria, we never had names for these conditions. But we knew them. The man who snored like thunder and woke up sweating? We called him ‘the one who fights the night.’ The woman who ate little but never lost weight? We said, ‘her body remembers hunger.’

Our elders didn’t need BMI charts. They saw the signs: fatigue, swelling, silence at dawn. They treated the whole person-not the fat, not the sugar, not the breath-but the spirit that carried them.

Today, we have machines that measure everything… but we’ve forgotten how to listen.

Maybe the answer isn’t more tests, but more time. More compassion. More community.

Health is not a number on a screen. It is the quiet strength of a mother who wakes up to feed her child, even when she can barely stand.

Let us not lose that in our algorithms.

Jane Lucas

January 8, 2026 AT 09:10my doctor never asked about sleep… now i’m scared to go back

John Barron

January 9, 2026 AT 06:03While the emotional appeal of this thread is understandable, the fundamental misstep lies in the conflation of anecdotal experience with clinical evidence. The assertion that ‘sleep apnea causes insulin resistance’ is not causal-it is correlational, and the directionality is not definitively established. Multiple confounding variables-including sedentary behavior, dietary glycemic load, and circadian misalignment-are systematically omitted from this narrative.

Furthermore, the recommendation to screen all obese individuals for sleep apnea ignores the cost-benefit analysis: the number needed to screen to prevent one cardiovascular event exceeds 500, making population-wide screening economically unjustifiable without symptom stratification.

One must also question the ethical implications of promoting pharmacological interventions like semaglutide as ‘miracle drugs’ without addressing the structural drivers of metabolic disease: food deserts, wage stagnation, and the commodification of health.

It is not the patient’s body that is broken-it is the system that fails to provide dignity, time, and resources for true healing.